For fungus gnat larvae, you should try using mosquito control bits (Bacillus thuringiensis subsp./var. israelensis); they are actually labeled for fungus gnat control as well as mosquitoes, and are perfectly safe to use indoors and quite effective. You can infuse them into the water that you use to moisten the medium prior to sticking cuttings to help prevent them from getting a foothold, and when watering the rooted cuttings later; you can also sprinkle the bits onto the soil surface and mist or water them to release the bacteria into the soil. They do decompose over time, but I try to keep them from sitting right against the base of the plant until it is fairly sturdy, and they never seem to do any harm.

The medium and its wetness level could be another problem. Many commercial mixes have proven to be disastrous in my experience (either due to pathogens or because of added fertilizer), so much so that I tend not to trust them in general. If the medium is actually sterile, then there’s a good chance any introduced pathogens will explode if they aren’t checked by naturally antagonistic microbes. I read a study once (Canadian, I believe) that found using dilute fish emulsion to pre-moisten peat moss well ahead of use (two weeks, if I remember correctly) promoted the growth of such antagonists and helped to prevent damping-off quite effectively. Personally, I tend to make my own mixes for both cuttings and seed starting; I use milled peat moss as the primary base, then add a smaller fraction of well-composted commercial manure/humus blend, or another deliberately non-sterile enriched humus of that sort, plus maybe a bit of clean sand (if available) or vermiculite (higher vermiculite for cuttings, little or none for seeds or other potting). The peat/decomposed humus core blend makes a more consistently reliable medium than anything I’ve found in ready-to-use form, and I suspect that the success is due to beneficial microbes that are likely present from the rotted manure/humus fraction.

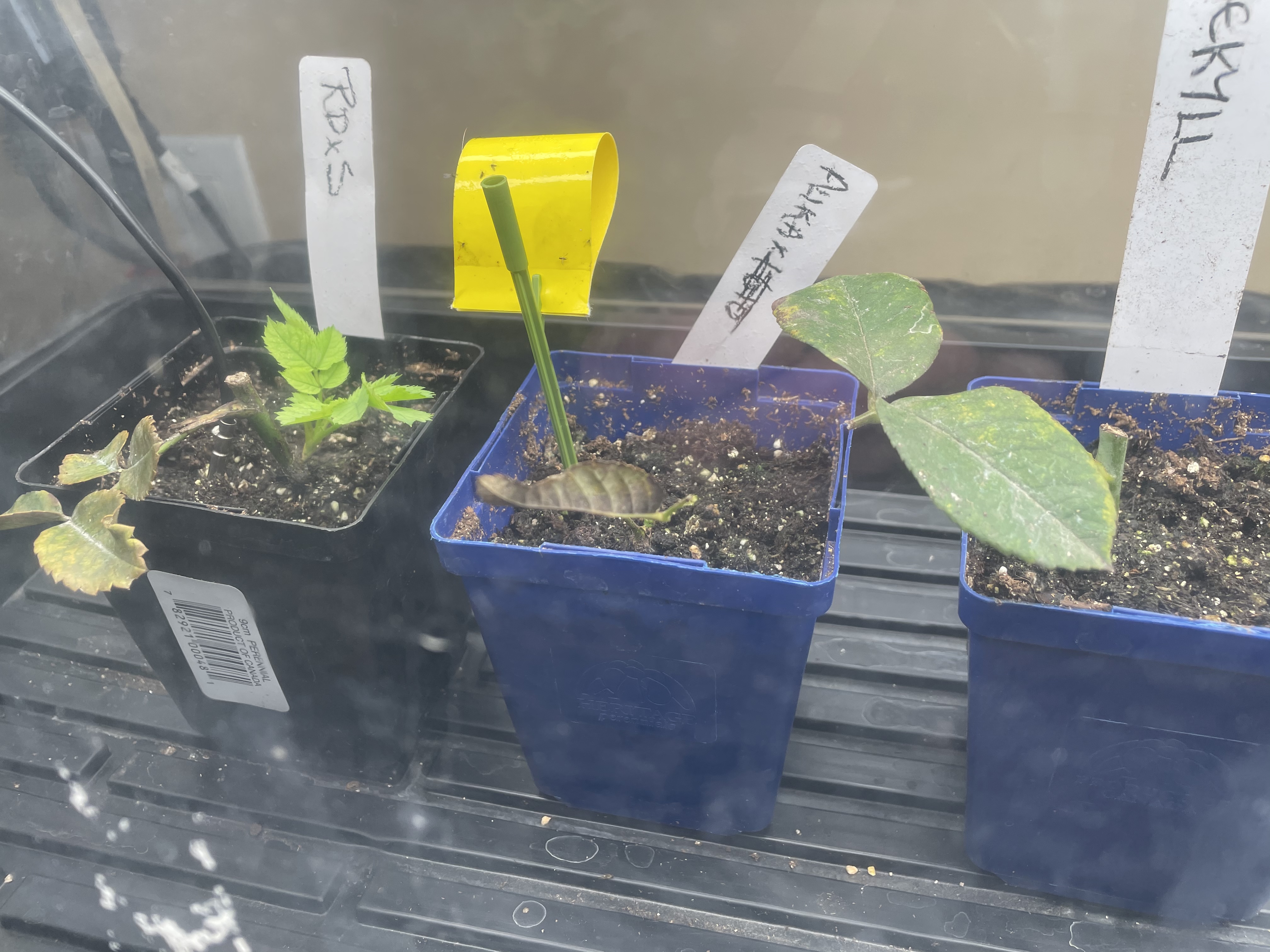

For cuttings, I tend to opt for two- or three-leaf cuttings (never just one leaf, unless there is no choice), with one additional node at the bottom with its leaf removed and a cut not far below that; I don’t do any wounding. If I’m sticking the cuttings directly into medium, then I pre-moisten the medium before putting it into the (hopefully clean) pot, pack the medium in lightly and dibble a hole, and then set into a zipper-seal polyethylene bag. If I’m especially worried about excess moisture, a folded paper towel or two underneath the pot usually helps to keep that from getting out of hand before I can intervene. Then, I dip the cut end into rooting gel (possibly not necessary–easily rooted roses generally can do without, as long as they keep their leaves); I place the cutting into the hole, pack the medium lightly around it, and use a spray bottle set to jet to squirt a bit of water directly at the bottom of the cutting, just enough to set it in place and ensure that it is moist enough (usually a few squirts). I mist the cutting’s leaves a bit and seal the bag, blowing some extra air in, and either leave it alone under lights or open the bag to mist occasionally. If extra water builds up in the bottom from condensation, or from my own misting, I carefully remove that if it threatens to wick back into the medium.

However, experience has taught me that for most roses, it often helps to place the cuttings in a glass/cup/jar in shallow water under lights or in a window sill, and let them callus in that prior to sticking as above (the water should be changed out every few days and the cutting’s bottom end rinsed). A well-developed callus seems to make for a pretty good initial barrier to pathogens, and the cutting usually survives better for me overall; I never use rooting hormones when opting for this method. Some roses that are particularly resistant to rooting may not callus in water, or will do so only very slowly, but if they do callus, their odds of successfully rooting and surviving are very good.

The most notoriously difficult-to-root types may still do best when stuck directly, though, especially if the medium is kept from being too moist; those might have trouble compartmentalizing wounds, and if they are placed in water to callus, they’ll quickly shrivel and die instead. They might also respond better to rooting over winter as dormant hardwood cuttings, the way European nurserymen used to produce them. I haven’t really experimented much with that.

Stefan