There are many cases where gene expression is altered by environmental conditions. Siamese cats, for example, are fully pigmented only on those parts of the body that are significantly cooler than core body temperature. At the opposite extreme, wingless fruitflies have an annoying habit of flying away when their larvae are maintained at a temperature of 75 °F or above.

There are also cases where some condition, possibly temperature, alters the pigment content of roses. I have two reports on the anthocyanin pigments found in garden roses:

Marshall (1976)

http://bulbnrose.x10.mx/Roses/breeding/MarshallArkansana1976.html

Eugster and Märki-Fischer (1981)

http://bulbnrose.x10.mx/Roses/breeding/EugsterPigments1991/EugsterPigments1991.html

According to Marshall, Rosa foetida bicolor contains only cyanin. To the contrary, E & M-F wrote, “The Austrian copper (R. foetida bicolor) contains surprising amounts of peonin, as already mentioned. If its progeny contain anthocyanins—which is not always the case—they always include peonin. An example is ‘Lady Penzance’ (Penzance, 1894), a shrub rose bearing coppery red flowers with a yellow center.”

Marshall reported that ‘Hansa’ contained some peonin, but more cyanin. According to E & M-F, “The richest source of almost pure peonin is the old shrub rose ‘Hansa’ (Schaum and Van Tol, 1905; Fig. 11). Its mauve-red flowers show what can be achieved by high levels of pure peonin!”

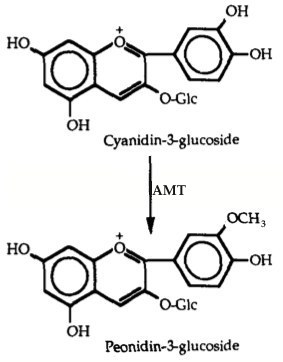

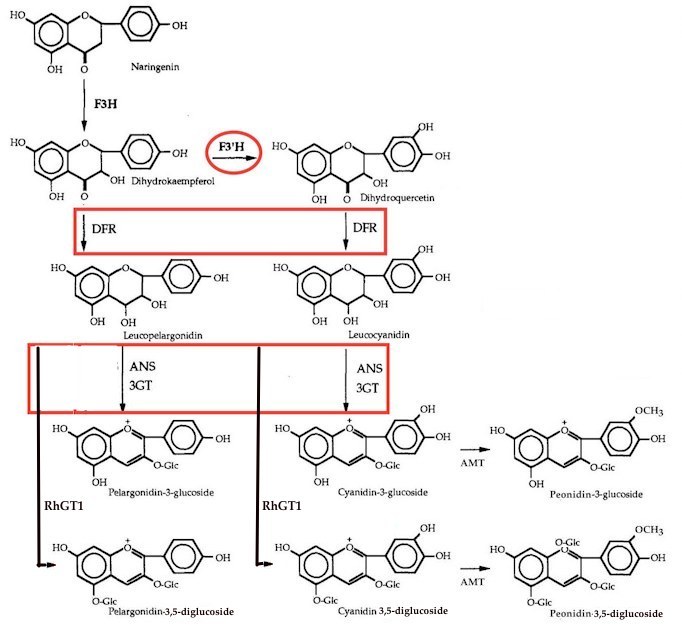

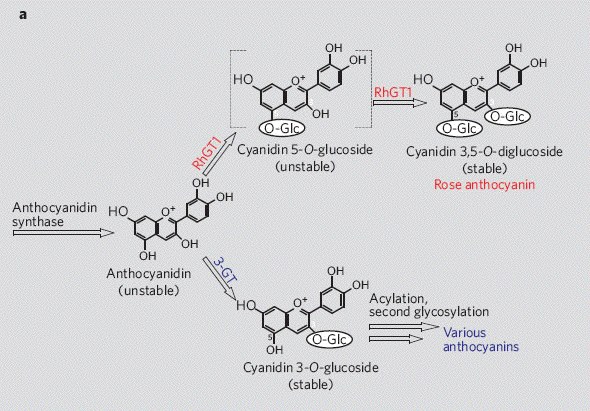

Eugster and Märki-Fischer: “Peonin is probably derived from cyanin. Whether the methylation occurs at the level of the cyanidin or only at its glucosides is unknown.”

In the cases I mentioned above, it appears that the enzyme that converts cyanin to peonin is variable in its expression. I can’t say for sure why it produces more peonin around Zurich, Switzerland than Morden, Manitoba.