An important point that Don mentioned is “practitioner of the art”. He also noted that such a person might not be able to reproduce the work based no the process patent. But my take on patents is that if it is obvious to practitioners of the art, it is not patentable under a regular patent. A patent requires novelty that is not obvious. If we collectively understand the power of CRISPR as a tool to modify genes by insertion, deletion and replacement, and the use of Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) using SNPs and other genetic markers, then we can say that what they did is nothing very special, just perhaps a lot of selection work. I presume that the big deal is that one way or a other they stacked in a lot of good traits including some disease resistances, desirable growth habit, excellent flower form, color, durability and so on. Maybe this process patent is a trial balloon for what Ball intends to do with the rose market when they get something novel such as resistance to RRD. For all I know, that may be what is special.

A sport is a trivial change in the rose, easily made by CRISPR technology and undetectable by standard molecular genetic tools. So I would want to claim it too, so that someone couldn’t engineer a pink or purple/black form and claim it as a sport.

The developers of CRISPR, and many other genetic engineers have tied themselves in knots in what is called the patent thicket. It gets so complicated that no one can figure out who owes what to whom in the way of royalties, permissions, licenses, and so on. This significantly drags down the market so that some country without many scruples can steal you into bankruptcy.

With the cheapness of GWAS markers and ways to detect them, the haplotype of a particular rose will be unique, even if Double KO is one parent and Rainbow KO is the other. BTW, RKO throws relatively a lot of minis in its rare selfs pool. I have half a dozen yellow/orange ones that I selected for good appearance relatively speaking. Rob Byrnes used one to make something that he registered I think.

The haplotype depends on the crossing over of chromosomes, so that any one chromosome becomes a mix of the parental ones, not seven of this and seven of that. Linkage doesn’t reach along a very big part of most chromosomes. Their lengths are measured in centiMorgans and 50 cM is a 50 % chance of a crossover happening between two genes. So a chromosome l00 cM long probably has 2 crossovers, or 1 or 0, or 3 or 4. That means in the next generation only only a fraction of what goes into an ovum or pollen grain is like the previous generation, if the chromosome pair was from two rather different parents. (Rather different is a relative term, for humans we can see minute bits that indicate that generations back we had an ancestor from a certain gene pool associated with a particular geographic region). For roses you could in principle detect the fraction of Austrian Copper or such in any of the Pernetianas and anything that actually descended from them. Likewise how much R blanda is in Carefree Beauty, how much R setigera is in Doubloons, Goldilocks and so on.

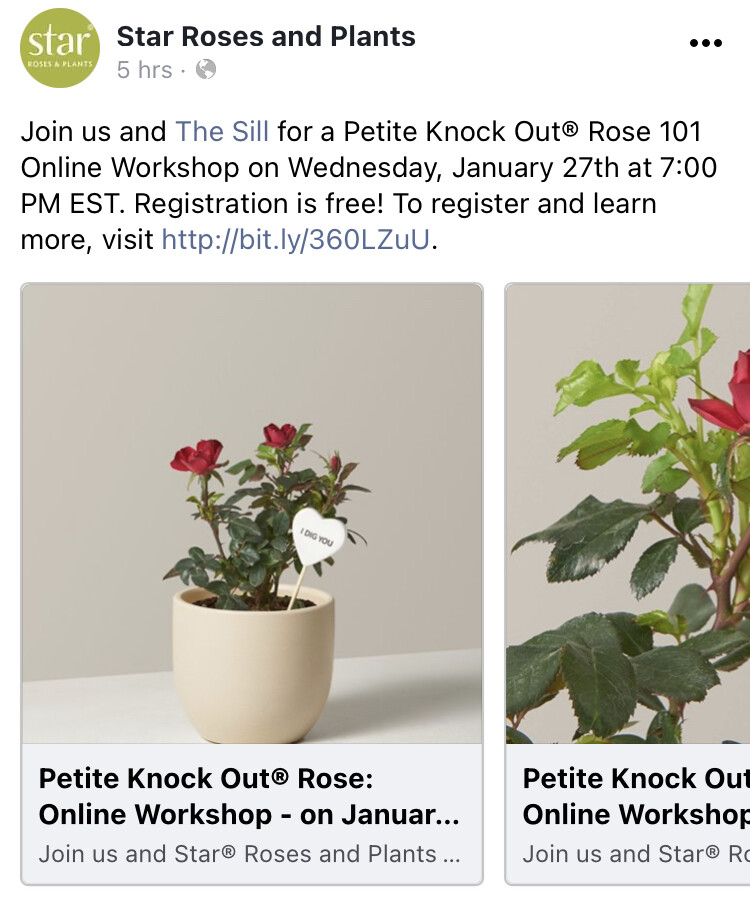

For the Petite KO it would be reasonable to predict that the location of the miniaturizing, or dwarfing genes is easily knowable if not already known.

Linkage disequilibrium, meaning that random assortment doesn’t happen for one reason or another, is what makes it hard to get all the desired traits together, or apart, like yellow color and B.S. resistance. BTW some Rainbow KO seedlings have that problem solved, if it was a real problem.

So I can see why Ball or whoever, wants us to not take advantage of all their hard work or luck. I don’t much like their approach and expect a good case could be made that their process patent is overbroad. But the problem is that you’d have to challenge them in court. That costs money. So they win by intimidation. Public opinion and private pressure is probably the most affordable tool.

My choice is to work with the nearly infinite available germplasm pool with what farmers might call landraces (well adapted, different, non-patent CVs, species and old favorites) mining them for interesting traits. I won’t run out of work or beautiful new roses in my lifetime.